The crowd was growing impatient, waiting for the doors to open. The hands seemed to be plodding wearily across the clock face. Finally, the usher throws open the doors, and people hurry to their seats. Soon, the theatre is full, and there’s not one empty seat.

Most people wear black, for here it is not a colour of protest but the colour of celebration. A true fan’s colours, flaunted with pride. When the lights inside the hall are dimmed, someone shouts ‘Thalaivaa’. This is greeted with claps of encouragement. The audience cheers even for the censor-board certificate that spells out the film’s name (‘Darbar’). And when the iconic animated credits begin to roll, it is the signal for fans to break into a frenzy.

For many, this is close to religion. First used in the 1992 film ‘Annamalai’, the credits appear as blue dots spelling out ‘super star’, followed by the letters R-A-J-N-I in gold. They swoop in to the sound of laser beams, and cheers of ‘Hey! Hey!’ in the background, set to a theme composed by Deva. The whoops, whistles and catcalls reach a crescendo when Rajinikanth enters the frame, donning khaki, playing the role of a cop. A bunch of people jump into the aisle between rows of seats and break into an impromptu jig. Someone throws popcorn kernels, a few hit me in my face.

Throughout the film, the hoots, claps and whistles continue and no-one in the hall shushes the crowd. Because all this is part of the experience of watching a Rajinikanth film on the day of its release; the audience seems to want more. But when it is over, the crowd quietly spills out onto the cold, wintery streets of Gurgaon. For a brief three hours, it seemed like this were Chennai. Now, the filmgoers’ behaviour is transformed; from speaking in Tamil they switch back to conversing in Hindi. The whoops and catcalls are gone, and they return to who they were – quiet, regular people going about their business, catching an autorickshaw or the Metro home.

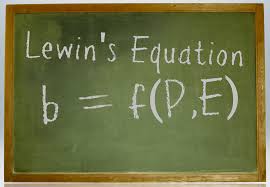

Behaviour is a function of someone in his or her environment, and people behave differently in different environments. This was first proposed by psychologist Kurt Lewin in 1936; it is now known as Lewin’s formula; B = f (P, E)

Many brands have leveraged this insight to craft their environment and tailor a brand experience to have consumers behave differently. For example, the environment at a Universal Studios, with its food stalls, theme rides and people dressed as characters from Universal movies, encourages visitors to relax, let their hair down, laugh and pass a few fun-filled hours with family and friends. And that’s exactly what the brand wants. Fathers enjoying being silly, taking kiddie rides and posting pictures on Facebook to tell everybody about the rollicking time they had. You can barely recognise the man in polka-dot shorts and a yellow Minion T-shirt as the formally-clad cubicle rat you see in office.

Think about the environment Apple creates inside their stores with the ‘Today at Apple’ program. Here, consumers can become students by discovering a new passion or taking their skills to the next level. It’s an experience that’s fun and enlightening. After all, people remember experiences and not product attributes, and that’s exactly what Apple wants.

Or consider the ‘outlaw biker’ image, first created during the Fourth of July riots in Hollister, California, in 1947, and cemented through early movies like ‘The Wild One’ and ‘Easy Rider’. This cultural motif was appropriated and suitably modified by Harley Davidson, nurtured through their HOG program to create a unique environment and experience for its customers. Owners of a Harley behave differently on their bike versus off it; their demeanour and self-image seem to mirror the brand’s personality.

Closer home, think about the environment a store like Big Bazaar creates for its ‘Sabse Saste 5 Din’ program, or an online store like Amazon with its Great Indian Sale. At retail outlets, the sight of shoppers pushing precariously-loaded carts may encourage other shoppers to buy more (and play the my-cart-is-more-full-than-yours game). The environment and the experience are designed to whip up a shopping frenzy where even the most tight-fisted shopper ends up spending more.

Lewin’s formula may be a simple concept but has far-reaching consequences. It teaches us that people behave differently at home, in their workplace, in social settings, and while shopping. It’s a useful thing to remember while seeking insights in focus-group discussions. How the consumer behaves is never static; context matters. Hence, the marketing message needs to account for context and get the desired behaviour or response from the target audience.

First published in Sunday Times dated 19 January, 2020